But sourcing parts from distant companies can have hidden costs. In a new study, Rob Bray, associate professor of operations at Kellogg, and colleagues analyzed supply chains for more than 600 car models. The researchers found that the farther a part traveled to reach the vehicle assembly plant, the greater the risk that consumers would report defects in that part.

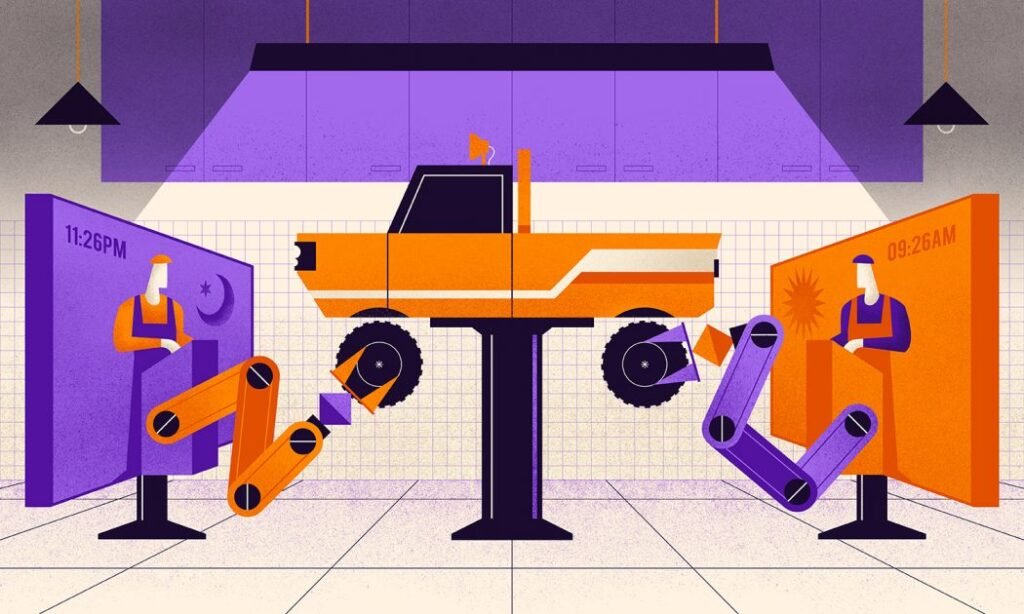

Why might distance lead to more defects? First, designing effective auto parts and improving them in subsequent iterations requires the supplier and assembler to communicate and learn about each other’s needs—something that’s most easily done face-to-face, Bray says. “Proximity facilitates that learning and helps you get better faster.”

Additionally, some activities, such as exploring a factory, can only be done in person – and these kinds of immersive experiences can make all the difference in product quality. Bray argues that an auto parts maker can gain a better understanding of the car model by, for example, touching the materials.

“A lot of supply chain management is really hands-on,” says Bray. “It’s not just a matter of discussing things. It actually does things and gets your hands dirty.”

The results of the study could be relevant to other industries, such as pharmaceuticals, where more than just profits are at stake. “If your part fails, people die,” Bray says.

Get auto part defect data

Bray and his former Ph.D Ahmet Colak, now at the Clemson College of Business, got the idea for this study while working on another project about auto recalls. The researchers gathered data on about 976,000 customer complaints about vehicle component failures collected by the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) over two decades.

The dataset provided a rare example of product quality assessments. In most industries, “it’s extremely difficult to get any empirical measure of ‘How good is the quality of a product?'” says Bray. But because NHTSA is responsible for determining when cars should be recalled, the agency consistently collects this information.

Colak then found another database, called Who Supplies Whomwhich tracked which auto parts companies supplied which parts for which car models—for example, who produced the rear stabilizer bars for the 2011 Toyota Corolla or the air duct system for the 2012 Mercedes-Benz A-Class. Overall, the database contained information for 1,765 suppliers to 68 car manufacturers worldwide.

Bray and Colak then searched for locations of vehicle assembly plants and supplier factories. With this last layer of information, they could answer the question: Does the distance a part travels make a difference in product quality?

For car suppliers and manufacturers, the closer the better

Bray, Colak and Juan Camilo Sherpa at McGill University used this data to compile the details of approximately 28,000 supply chains for 685 car models from 1999 to 2014. They then cross-referenced this data with customer defect reports for every component in the United States.

Parts from distant suppliers seemed to fare worse, the team found. Increasing the distance by an order of magnitude—say, from 100 to 1,000 miles away—was associated with a 3.9 percent increase in the defect rate. The team estimated that if the typical car manufacturer were to replace its component supplier with the most distant supplier, the defect rate for that component would be expected to increase by 1.5-2 percent on average.

However, this correlation did not mean that distance necessarily caused the defects. So the researchers then put the data to a more rigorous test.

They analyzed all cases in which a carmaker had moved a factory location — motivated, for example, by tax breaks or other government incentives elsewhere. Such relocations occurred 79 times during the study. Sometimes the factory ended up closer to suppliers after the move, and sometimes the opposite.

“This was kind of a natural experiment,” says Bray. If some factor other than distance was causing the failures, the researchers reasoned, then the defect rate should not increase just because a supplier moved further away.

But, as expected, when the distance between the suppliers and the car manufacturer increased, so did the defect rate. And when the distance was reduced, the defect rate also fell.

And the per-mile effect was three times stronger if the supplier was based in a different country than the assembly plant, even if the distance was the same. “A mile domestically is not as harmful as a mile internationally,” says Bray. Why; He speculates that perhaps the road infrastructure in other countries is less developed, making components more likely to be damaged along the way.

Because supply chain distance leads to more defects

One reason researchers suspect distance may lead to more defects overall: collaborating on component improvements is easier face-to-face.

To test this hypothesis, they decided to study how much defect rates for components changed over time. After all, the work of designing and building a car does not end with the first model. Manufacturers continue to work on improving product quality with each new release. Thus, if the relationship between distance and quality was due to cooperation, then product quality should have increased faster when the supplier was closer to the assembly plant.

So the team looked at what happened to defect rates as car manufacturers and suppliers worked together to improve components over time — for example, making improvements to the alternator between the 2012 and 2013 Honda Civic models.

What they found supported the collaboration hypothesis: the closer the supplier was to the car manufacturer, the faster the failure rate for that supplier’s part dropped relative to subsequent releases. (However, the researchers could not rule out other explanations for the relationship between distance and defects—for example, that car manufacturers can better judge the quality of nearby companies, so nearby suppliers tend to be better, all else equal. )

The importance of working closely together makes sense, says Bray, given the complexity of the information that needs to be conveyed. “The supplier doesn’t really understand the rest of the car, and the automaker doesn’t really understand that part,” he explains. “Both have partial information.” If the parties are closer, it becomes much easier to bridge this gap.

Collaboration appeared to be particularly critical for certain types of cars and parts. For example, luxury cars saw a larger jump in defects as mileage increased, possibly because they were more complex and contained more custom components. The same was true for components with more subcomponents.

Would shorter automotive supply chains save lives?

While Bray won’t go so far as to recommend car companies buy parts closer to home, he hopes they see this study as a warning. “I want them to know that added cost” to product quality, he says.

How much do these small increases in defect rates really matter to car companies? Enough, argues Bray. Given how mature the auto industry is, he says, “a 1 percent improvement”—either in quality or performance—”is very difficult these days.”

And small gains in component quality can lead to big savings for society, as some defective components can lead to road accidents.

Cutting all supply chain distances in half would reduce conflicts by 0.37 percent, his team estimated. When the researchers calculated the costs of accidents to society, including health care and property damage, as well as congestion and pollution from traffic congestion, the amount saved amounted to about $2.4 billion annually.

Dollars and cents aside, Bray reiterates that people’s lives are at stake. “If your phone breaks, it’s okay,” he says. “But if your brakes fail, it’s no good.”

#money #investing #finance

#money #investing #finance