Our climate future depends on the choices we make now.

As has been widely reported, 2023 was officially the hottest year on record. For the last twelve months they have exceeded 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels (the scientific base period used for global warming). That bleak milestone has led some critics to say that reaching net zero carbon dioxide emissions by 2050 is impossible. Doomsayers even claim that it is too late to stop climate change. Fortunately, science and economics show that these narratives are completely wrong. However, they are dangerous because of the regression and inertia they promote. Exceeding the 1.5°C limit makes the imperative for climate action stronger, not weaker.

Since we hit 1.5°C in 2023, is net zero dead? No.

While global temperatures exceeded the 1.5°C level (years like 2023 with a strong El Niño are usually warmer than average) and may do so regularly into the 2030s, this does not signal the end of net zero or 1.5°C pathways. Many misunderstand what 1.5°C means in a climate scenario. When the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world’s leading authority on climate change, refers to 1.5°C pathways, refers to the temperature in 2100. Net zero by 2050 represents a path that balances the social, economic and technological realities of decarbonisation with an emissions trajectory that will hold global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels in 2100. It is understood that a giant asteroid that wipes out civilization could reduce emissions directly, but understandably, few would see this as a desirable path.

It is noteworthy that in The latest IPCC report almost all “1.5°C aligned” scenarios actually exceed 1.5°C at some point in the 21st century before returning to 1.5°C or below at the end of the century. This is due to the unfortunate events that: exists some degree of inertia in the climate system and we are behind in reducing emissions. Later temperature declines in these scenarios depend on net negative emissions or the use of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) methods. Essentially, in these scenarios we have borrowed against the ‘carbon bank’ and have to pay it back through relocations. The extent to which these scenarios exceed 1.5°C is called exceedance. High overshoot scenarios are more costly due to higher CDR investments and riskier for reasons discussed below.

Are we powerless to stop climate change once we reach 1.5°C? No.

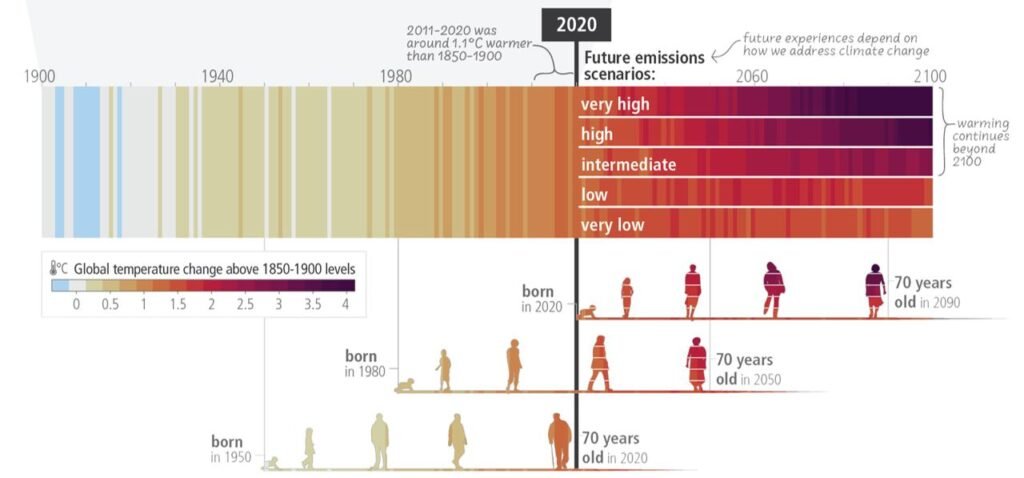

Extensive scientific research has shown that above 1.5°C, Climate risks are increasing in severity and potential climate tipping points are becoming more likely. However, the climate system is remarkably complex, and we cannot know the exact temperature when a tipping point will come, such as when Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which currently makes Western Europe much warmer than its latitude suggests, will collapse. Assessing climate impacts is a game of odds, and warmer temperatures bring with them greater chances of dangerous consequences. The planet is not like the bus in the movie “Speed”, which will explode once a given speed is reached.

Perhaps a better analogy for climate impacts would be an ice cube in an oven. To figure out how much the ice cube would melt, you need to know how hot the oven is and how long the ice cube stays in the oven (and the properties of the ice cube). Likewise, climate risks are not just a function of temperatures above pre-industrial levels, but how long we stay there. A hundred years at 1.5°C will be worse than a year at that temperature.

Climate tipping points and potential trigger temperatures.

Returning to tipping points, despite their name, they are not binary. Even if they are triggered, how quickly they occur depends largely on how high the temperature rises and how long it stays elevated. About 400,000 years ago, at temperatures similar to today’s, Greenland lost almost all its ice. Does this mean that Greenland’s tipping point has already been reached? Maybe. However, even if it has, the ice could melt in 1000 or 100 years. Sea level rise in the first scenario would be much more adaptable than in the second. Therefore, we should do everything we can to slow down the already active tipping points and prevent the ones we haven’t hit by avoiding further global warming.

Every fraction of a degree we mitigate is a win for the planet, as is every reduction in time spent in high temperatures. There is no magic threshold that will make 1.5°C the endpoint of our climate fight. If we can’t stay below 1.5°C, we should fight for 1.6°C.

Are net zero runs still useful even above 1.5°C? Yes.

In recent years, pure nullification paths have become some of the most studied scenarios ever. Complex socio-economic models have explored different decarbonisation pathways for individual sectors and the economy as a whole. Businesses, financial institutions, municipalities and nations around the world are developing detailed net zero transition plans. This work does not suddenly become useless the moment we reach 1.5°C of warming. Global warming will not stop until we reach net zero emissions, so the decarbonization strategies that have been developed remain critically important whether net zero is reached in 2050 or 2060. Furthermore, organizations with the best transition plans will be better off to succeed in a low carbon future.

Net zero pathways can catalyze climate action by creating a common goal in global business and trade. Financial institutions have incentives to help their customers decarbonize in order to achieve their net zero goals, as do buyers with their suppliers. Countries are incentivized to implement policies to reduce emissions and work with other states to meet their Nationally Determined Contributions (their climate targets under the Paris Agreement) through activities such as internationally transferred mitigation effects (ITMOs) and carbon markets.

Are there reasons for optimism in our fight against climate change? Yes.

Despite the fact that emissions and temperatures are rising, there are promising signals just below the surface.

In 2010, climate scenarios predicted business as usual (BAU). about 4 C of warming by 2100. Now, due to much stronger policies and advances in green technologies, this The BAU temperature rise is closer to 2.6-2.8C (still dangerous, but >1 C reduction in our orbit). Over 90% of the world is now covered by zero commitment. Net zero has become mainstream in the private sector as well, with thousands of companies and financial institutions are committing to decarbonisation and forming strong alliances such as the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net-Zero (GFANZ) and We mean Business Coalition.

As discussed above, climate tipping points have a justifiably negative connotation. However, there are also positive political, economic and technological tipping points. At COP 28, nations collectively pledged to triple renewable energy production by 2030which would be a huge step in reducing emissions and returning to a net-zero trajectory by 2050. In 2023, Investments in renewables exceeded investments in fossil fuels, and globally nearly 80% of new energy infrastructure installed comes from low-carbon sources. Installation of renewable energy sources has increased by 50% from 2022 to 2023 and above a hundred nations may have the peak of fossil fuel use has already passed.

Current and projected development of RES

This progress also reveals the benefits of driving for net zero. Large long-term capital allocators need policy stability and clarity if they want to invest in the development of a new power plant or bring a new technology to market. A clear zero mandate encourages the private sector to innovate faster and accelerates the development of green solutions.

As the international community looks towards COP 29 and beyond, the commitment to climate action must remain unwavering. Our collective efforts to mitigate every fraction of warming and to decarbonize all sectors of the economy are vital. The path to net zero, though fraught with obstacles, remains our most promising path to a resilient and sustainable future.