To Nicole Stephens, professor of management and organizations at the Kellogg School, Bridges’ story highlights a blind spot in how some organizations still view diversity. “I think a lot of schools and workplaces are focused on the idea of getting people in the door and increasing diversity based on race, socioeconomic status, gender and so on,” says Stephens. “But much less attention is paid to what happens after we get people in the door.”

In a recent study, Stephens and her colleagues sought to fill this gap by exploring the diversity of people’s actual interactions at American universities. They asked: Does having a diverse student body actually lead people to interact with people of different social class and racial or ethnic backgrounds? And when these intergroup interactions do occur, do they actually produce tangible benefits for students, such as enhancing a sense of belonging or improving academic performance?

Stephens worked with Rebecca M. Careyformer Kellogg postdoctoral fellow who led the study and is now at Princeton, Sarah SM Townsend at the University of Southern California and MarYam G. Hamedani at Stanford. Together, they recruited university students to provide detailed accounts of their daily social interactions and how those interactions made them feel.

The data suggest that simply having a diverse campus is not enough in itself to enhance interactions across social differences. But it wasn’t all bad news. Among those with underrepresented backgrounds—such as racial minorities and those from lower social classes—students who had more diverse encounters reported greater inclusion and, therefore, performed better academically.

What happens when we interact with people who are different from us?

When thinking about the interactions between different groups of people, it is important to understand one of the most frequently observed phenomena in the social sciences: homophily. This is the notion that people tend to prefer and associate more often with people who are similar to themselves.

“Similarity feels comfortable,” Stephens explains. “It’s easy. It feels natural. It’s nice to have others who know what your background is like and who have common assumptions about how to be a good person or how to be a student.”

Homophily helps explain why exchanges across class or race boundaries tend to be relatively uncommon—and why such interactions often evoke emotion discomfort, stress and anxiety.

But while these interactions may be difficult in the moment, they also have the unique potential to help promote understanding and empathy. Decades of research have shown that intergroup contact—or engaging people in meaningful interactions with people from different social groups—is “the gold standard for reducing prejudice,” says Stephens.

So, to what extent will people resist the forces of homophily, and are the positive long-term effects of such encounters enough to make the immediate experience of discomfort worth it?

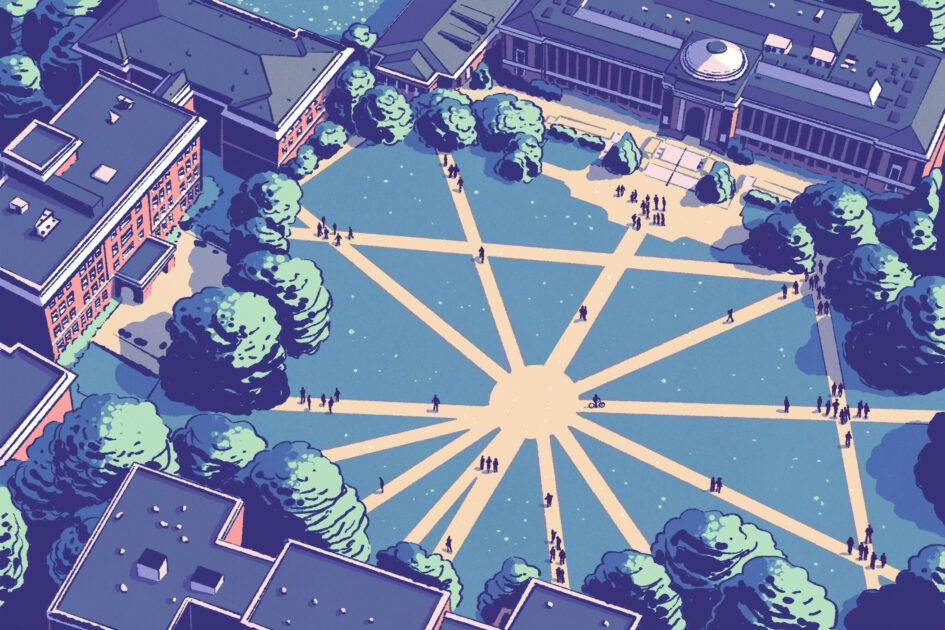

Stephens and her colleagues knew that the modern university was a natural laboratory for studying these questions, given the extensive efforts universities have made to get students from marginalized groups in the door. “In a country that is highly segregated like the United States, universities are one of the few places where people have the opportunity to have meaningful and meaningful interactions across social class lines,” he says.

The researchers recruited 552 college students at two North American universities to complete a series of daily surveys in which participants listed their “most meaningful” interactions in the past 24 hours, as well as their counterpart’s gender, race, and social class in each one. INTERACTION. (Social class was measured by the perceived income and education level of the counterpart’s parents.) Students also reported how stressful, threatening, and rewarding this encounter felt to them, and whether they felt they belonged on campus that day.

Students were asked to complete this daily survey task eight times during their first academic term. The researchers then coded each interaction as either same-race or cross-race and either same-category or cross-category. (For example, if an Asian student from a middle-class background noted a conversation with a classmate she believed to be Black and lower-income, the interaction would be coded as cross-racial and cross-class.)

The resulting data set included a total of 11,460 interactions for the researchers to analyze.

At the end of the academic year, students completed another survey that focused on their feelings of inclusion and belonging at their university. This was done by asking students to indicate how much they agreed with statements such as “[This university] it’s a place for students like me.”

Diversity does not lead to diverse interactions

The researchers first estimated how often interactions between classes and races should be expected due to pure probability, based on the demographic makeup of the campuses and students in the study. For example, if at one university 43 percent of the student body were students of color, then the average white student there would be expected to engage in interracial interactions 43 percent of the time. Using similar calculations for each group, the researchers could estimate the total proportion of interactions between classes and races that would be expected by chance. They then compared these hypothetical numbers to the actual rates at which students reported interactions between classes and races.

Overall, the researchers found that there were 15 percent fewer cross-class interactions and 27 percent fewer inter-race interactions than would have occurred by chance alone.

In terms of cross-class interactions, those from lower- and working-class backgrounds were more likely to engage in cross-class interactions than students from middle- or upper-class backgrounds.

When it came to interacting with students of a different race, certain groups were especially likely to gravitate to people like themselves. Black, Native American and Latino students (grouped together in the study) reported interacting with white or Asian counterparts less than a third of the time, even though white and Asian students made up 73 percent of the university’s collective student body. While both white students and Asian students were also disproportionately likely to seek out those of the same race, compared to what the interactions would look like if they happened by chance, the trend was much less extreme than with black, indigenous and Latinos.

Taken together, the results show that “even when these kinds of interactions are possible, people don’t take full advantage of that diversity,” says Stephens.

Consistent with previous research, students tended to come away from their intersectional and interracial encounters feeling less empathy for their counterpart than in same-class and same-race interactions. They also tended to believe that these encounters had not gone as well as same-class and same-race interactions.

But even though students generally avoided many cross-class and cross-racial interactions, these uncomfortable exchanges seemed to confer real benefits on those from underrepresented backgrounds.

For students from lower grades and students who were Black, Native American, and Latino, those who participated in more intergroup interactions tended to have a higher GPA at the end of the school year. (This result held even after controlling for students’ prior academic performance, suggesting that it was not the case that higher-achieving students simply gravitated to more diverse social groups.) The same students also reported feeling greater feelings of belonging.

On the other hand, the between-group interaction did not appear to have any effect on either the academic experience or the achievement of middle- or upper-class or white or Asian students. However, the researchers suspect that these students also benefited from these interactions in ways not measured in this particular study (eg, appreciation of diversity or complexity of thought).

How embodied emotion leads to academic success

Why did diverse interactions benefit students from underrepresented backgrounds but not their more advantaged peers? The researchers point to several possible explanations.

First, the data show that these interactions led underrepresented students to feel more like they belonged on campus. “If you come from a background where family members didn’t go to college and you’re not familiar with the upper-middle-class context of higher education, then when you walk into that space, it’s very normal to feel like an outsider,” says Stephens. Decades of research have shown that these feelings can hinder academic performance by making students less comfortable and more stressed—so when disadvantaged students feel more at home, their performance will naturally improve.

It is also possible that these interactions gave underrepresented students the opportunity to gain “cultural capital,” an understanding of the unwritten rules that often dictate who succeeds and who fails.

“You can learn, for example, how to interact with professors, how to ask questions in class, how to look for the resources you need to succeed,” Stephens explains. “These are the things you can learn from cultural insiders who take for granted that they belong. These are people whose parents have trained them from the age of three on how to exploit resources and how to influence the situation to get what they want. So learning from these people can be extremely beneficial.”

However, the low rates of organic cross-cultural interaction suggest that students are unlikely to seek out different social groups without some prompting.

Stephens recommends that universities randomly group students into dorms or class projects rather than letting them choose roommates or project partners on their own, to counteract the pull of homophily. (Indeed, he is currently conducting a longitudinal intervention to assess the potential benefits of assigning college students to engage in meaningful interactions with people from diverse social backgrounds.)

“We need to think about how to create intentional systems to make sure that people actually interact across differences and have the ability to benefit from those differences,” he says.