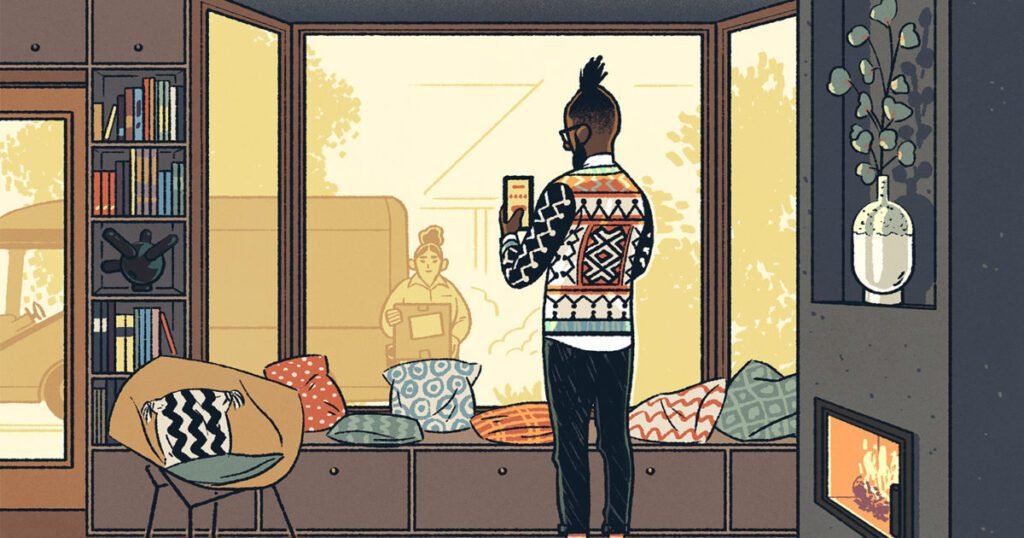

Imagine you are working on a project for a client. You want them to notice your effort, so send frequent updates as you complete each task.

This is called “functional transparency” — the idea is that “if you can see how hard I’m working, then you’ll appreciate it more,” he says Rob Bray, associate professor of operations at Kellogg. Additionally, customers may appreciate feeling in the loop.

But transparency can have a downside. After all, if you show customers every step, they may also notice long delays between progress reports. “You’ll also be airing dirty laundry,” Bray points out.

So how can you maximize the benefit of this transparency while minimizing dirty laundry?

A recent study by Bray showed that the timing of updates matters. He analyzed a huge data set of package delivery records from the e-commerce giant Alibaba in China. When customers received frequent status updates on their online orders toward the end of delivery, they tended to rate the service highly. But if the activity was concentrated near the beginning and followed by inactivity, the scores tended to be lower – even if the overall delivery time was the same.

He suspects this pattern arose because customers pay more attention to what happens late in the process—a phenomenon known in psychology as the edge rule.

“Typically, people remember the end of the experience,” says Bray.

The lesson for companies, he says, is that customers may be happier with services when more updates are offered toward the end. Or perhaps companies should invest more resources in improving the last phase of product or service delivery, as customers pay more attention to these steps.

“Companies should be aware of this peak effect,” he says.

A data mine for operational transparency

Bray’s study arose out of a serendipitous chance. Alibaba Group’s logistics business Cainiao has agreed to allow researchers from the Manufacturing and Service Operations Management Society (MSOM) to analyze more than 100 gigabytes of data on packages delivered to China in 2017.

“It’s an insane amount of data,” says Bray.

MSOM members had about 10 months to study the data set, with the best paper winning a prize. Bray’s research came in first place.

Going into the contest, Bray didn’t have a clear question in mind. So, he started looking into the data. Each delivery record showed when the product was ordered, shipped from a warehouse, picked up by a carrier, entered or exited a facility, scanned for final delivery, and received by the customer. On average, a file included about seven delivery-logistics actions (not including ordering and receiving the package from the customer). Customers could track real-time updates on mobile apps.

Bray could investigate whether the timing of updates affected customer perceptions of service quality.

But what piqued Bray’s interest was the rating customers gave each delivery. Normally, in logistics data sets, “it’s just, ‘This inventory moved from here to here to here to here,’ period, and that’s all you know,” he says. “Was it good or not good? I don’t know.” But having the scores was “remarkable,” he says. “That’s what makes this data set so unique.”

Bray realized that the data offered a detailed real-world example of operational transparency and wondered if this transparency benefited the company. The company’s assumption was that clients would appreciate receiving updates about the work being done on their behalf. But, of course, the flip side is that customers would also notice long periods of inactivity.

In other words, customers could see activity, but also periods when nothing was happening. And since each step was time-stamped, Bray could investigate whether the timing of updates affected customers’ perceptions of service quality.

Gradual results

Bray began by analyzing all entries for a specific type of action — shipping from a warehouse, for example, or entering a facility — for 4.68 million packages. He then studied the scores for the overall delivery that included this action. Deliveries were rated from 1 to 5, with 5 being the best.

To his surprise, a neat plan emerged. Deliveries with a score of 1 or 2 tended to have actions taken slightly earlier than those with a score of 3. Those scoring a 3 tended to have actions taken earlier than those with a score of 4. And the deliveries with the best scores tended to they are those for which that particular step in the process occurred later — that is, closer to delivery.

“I was amazed,” he says. “What was dramatic was the perfect order.”

To investigate further, he analyzed the relationship between the timing of an action and the score. For example, it could calculate the average score if an order entered the facility, say, 20 percent of the way through the delivery process versus 80 percent of the way through.

Bray found that moving any activity from the 15–20 percent window to the 80–85 percent window was associated with a 0.01 increase in score. And if the average time of all actions was at 80 percent of the process rather than at the 20 percent mark, the average score was 0.05 points higher—on par with the score increase from expediting delivery by about one day.

However, these links did not prove that later action times actually caused higher scores. To gather more evidence, Bray took advantage of the fact that activity usually slows down on the weekend. Packages ordered on Friday tended to be quiet at the beginning of the process. In contrast, those who arrived on Mondays tended to be quiet towards the end.

As expected, packages that suffered an early weekend lull received a higher average score.

Happy customers

Why is this happening;

Bray can’t say for sure, but he thinks the pinnacle rule applies. Essentially, this means that people remember the end of an experience more than the beginning.

In older study, the researchers illustrated this phenomenon with a simple laboratory experiment. Each of the 32 male participants performed an unpleasant action twice: placing their hand in a tub of water chilled to 57 degrees Fahrenheit for one minute. During one of the two tests, the participant was told to leave their hand in the tub for an additional 30 seconds while the water became a few degrees warmer but was still uncomfortably cold.

Then each had to choose whether they would prefer to repeat the one-minute or 90-second test. About two-thirds preferred the latter, even though the total amount of suffering experienced would be greater.

The result is unimaginable because adding an extra unpleasant step will worsen the overall process. But participants appeared to place more weight on the last 30 seconds of their experience.

When people wait impatiently for a package, a similar effect could occur. Imagine a customer who receives several early updates and then a long lull, Bray writes: “After seeing the package zip through three facilities in two days, you expect it to arrive at any moment, only to suffer an additional four days delay. Moreover, the ambitious beginning makes you more aware of the ensuing silence.’

Then consider another client who receives incremental updates towards the end. While seeing little progress at first is “worrying,” Bray writes, the person may simply assume the company isn’t reporting every step. Later, he speculates, “you’re reassured by a steady stream of updates. That latest rant is fresh in your mind when you give the delivery the best possible score.”

Extra credit

How should workers and companies interpret these findings?

It’s probably not feasible for a delivery company to take more logistical steps towards the end. But it may not be necessary to list every action near the beginning, Bray says. Or maybe the company will have to put a lot of effort into getting the final steps done quickly.

Similarly, if, say, a consultant is writing a report for a client, it may be better to provide more updates as the project nears completion than to send a series of early updates followed by silence.

When you’re judged on your performance, Bray says, “you tend to get more credit for the work you’re doing right before the evaluation period.”

Selected Faculty

About the Author

Roberta Kwok is a freelance science writer based near Seattle.

About the Research

Bray, Robert L. 2019. “Operational Transparency: Show When Work Is Done.” Working paper.