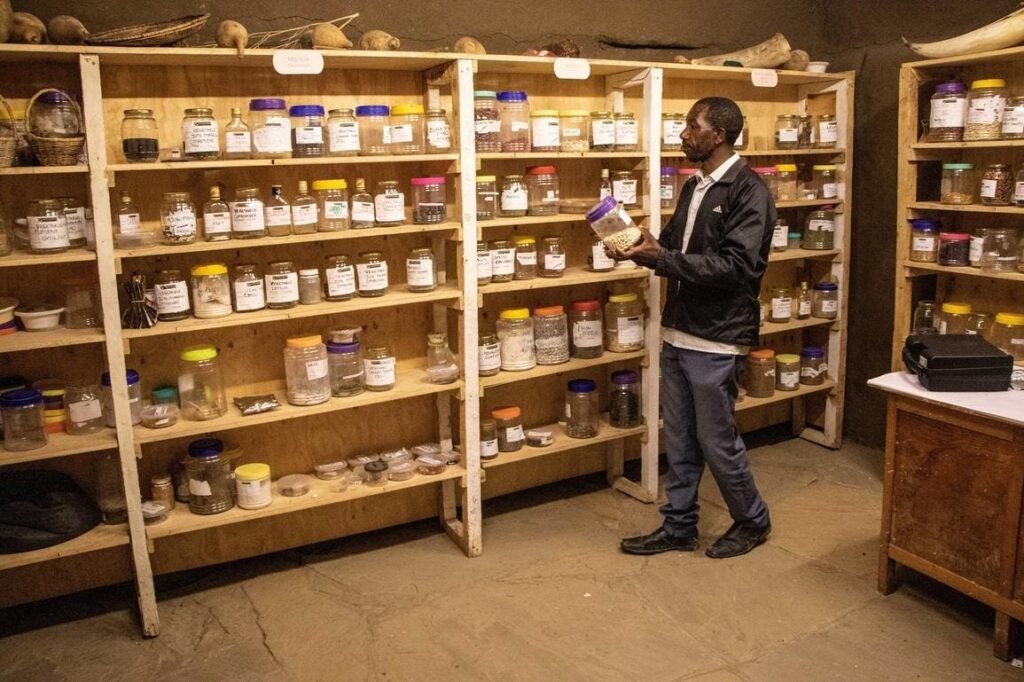

Seed Savings Network seed bank in Gilgil, Kenya. The Kenyan NGO Seed Savers Network works with … [+]

On August 27thAfrican leaders of faith, agriculture and the environment have come together to launch an unusual declaration. Their open letter was addressed to the “Gates Foundation and other financiers of industrial agriculture.” He charged these financiers with promoting a type of corporate, industrial agriculture that does not respect African ecosystems or agricultural traditions.

The letter was organized by the South African Community Environment Institute (SAFCEI) and has over 150 signatories. Its launch was timed to influence the Africa Food Systems Forum in Kigali, which starts today. Partners of this conference include the Government of Rwanda, AGRA, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and other charities, agribusiness companies and aid organizations.

The open letter is particularly aimed at two related organizations. The Gates Foundation is primarily known for its investments in public health, but it has also made significant inroads into agriculture. In Africa much of this work is carried out through the Nairobi-based AGRA (formerly known as the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa). The Gates Foundation is a co-founder and the largest donor to AGRA. Other major donors include the UK and US governments.

Under a basket of policies dubbed the “green revolution,” AGRA, the Gates Foundation, and similar institutions sought to greatly increase the use of synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and commercial seeds in Africa. This has focused on developing new seeds and a vendor network. The goal was to dramatically increase agricultural production in order to reduce hunger and increase farmers’ incomes.

But by AGRA’s own admission, this failed in its aim to double crop yields and incomes for 30 million farmers by 2020. In fact, some critics argue that AGRA has made things worse.

According to one external review by Timothy A. Wise of Tufts Universitysevere hunger in AGRA countries increased by 30% between AGRA’s inception and 2018. Crop yield increases have been modest and, where present, not always enough to cover the higher costs of growing with commercial seeds and agricultural inputs . Dependence on fertilizers has increased the debt and financial insecurity of smallholder farmers who make up the majority of farmers in Africa. In some cases, limited yield increases have also been temporary, as soil fertility has declined due to monoculture and fertilizer use. For example, Ethiopian farmers “will say the soil is degraded, meaning it cannot produce food” without synthetic fertilizer, reports Million Belay of the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA).

There have been negative results, says Belay. For example, Zambian farmers who have become indebted due to purchases of synthetic fertilizers have had less money for food and for the education of their children.

In other words, many farming families are poorer and hungrier than before, while the land itself is less productive.

Although AGRA failed to double farmers’ income and yields, it succeeded in changing government policies for the worse, according to Belay. These include loosening regional biosecurity and fertilizer regulations, Belay says. In Kenya, farmers can now cope jail time for storing or sharing seeds;.

A new AFSA fact sheet states that AGRA seeks to place advisers in government offices and “directly creating policies at the continental, national and local levels”. This includes a new ten-year policy for agricultural investment in Zambia.

Overall, it is a highly commercialized, elite and often rich global vision of African agriculture. Tim Schwab writes The Bill Gates Problem: Quantifying the Myth of the Good Billionaire“Rarely, however, do the targets of Gates’ goodwill, the world’s poor or small farmers, have a seat at the table. In the case of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, or AGRA, the allies include a range of corporate partners: Syngenta, Bayer (Monsanto), Corteva Agriscience, John Deere, Nestlé, and even Microsoft.” AGRA has been criticized for helping its agricultural partners expand in Africa.

When it comes to harmful farming models, AFSA’s Belay acknowledges that the Gates Foundation is not solely responsible. “We can’t blame everything on Gates,” he says. It points more broadly to the narrative spread in rich countries that food cannot be produced without agrochemicals, new seeds and market agriculture, despite the severe impact on land and limited effects on reducing hunger. “This is a powerful narrative, and they have shaped African universities in this image,” argues Belay. It also highlights African governments’ spending on green revolution approaches.

One reason this industrial-agricultural narrative has prevailed is that it seems intuitive that producing more food equals feeding more people. This myth is both persistent and dangerous. The world has more than enough food for everyone. Hunger persists due to poverty and inequality, exacerbated by conflict and climate change.

To give just one current example, Victoria Tanimonure of Obafemi Awolowo University’s Department of Agricultural Economics says that parts of Nigeria experiencing famine are exporting food to neighboring countries. This pattern has also been seen in previous famines, such as UK potato exports during the Irish Potato Famine.

So, It’s not underproduction that’s the problemand technical solutions alone are insufficient – no matter how loudly agribusinesses proclaim that their products are essential to feeding the planet.

The enormous power of the Gates Foundation

A bigger criticism concerns the enormous power of the Gates Foundation. Schwab writes, “In this deeply unbalanced, one-sided discourse, there has been little room for serious public debate and little recognition of what the foundation actually does. Bill Gates doesn’t just donate money to fight disease and improve education and agriculture. He uses his vast wealth to gain political influence, to remake the world according to his narrow worldview.”

Schwab also criticizes the great influence the foundation now has on international development journalism, including agriculture in low- and middle-income countries. He believes that the foundation’s extensive grant-making and training of journalists contributed to its monopoly of conversation and unwillingness to hold this powerful organization accountable. (I have received funding from the Gates Foundation, through programs administered by the United Nations Foundation, the European Center for Journalism and the Solutions Journalism Network.)

The foundation has dramatically reshaped global health and development, often for the better. However, it should not be immune to criticism. As Mariam Mayet, of the African Center for Biodiversity, told Schwab in The Bill Gates problemthe Gates Foundation has mobilized so much funding and influence for an industrial model of agriculture that it has crowded out alternatives. “No other future could be born because of the Gates agenda and those he funded and stood in the way of – whatever transformation and transition was possible that could result in less social exclusion, less inequality, less poverty, less marginalization of the already vulnerable communities,” Mayet said.

An alternative type of agriculture often touted by environmentalists is agroecology, a holistic approach to agriculture that seeks to preserve ecological health as well as local control. In practice, this can often include minimizing synthetic fertilizers and prioritizing soil health.

Belay gives specific examples of successful non-industrial agriculture, such as a Kamapala training center where young farmers exchange information about producing biofertilizers themselves, rather than turning to expensive products that acidify the soil. Nutrient-rich natural ingredients can include cow urine or discarded bones. Individually, these programs may be small-scale compared to the market reach of multinational agribusinesses. But “there are so many methods,” Belay points out.

What compensation might look like

Enock Chikava, Director of Agricultural Delivery Systems at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, states: “We believe that African farmers deserve and must have access to a range of affordable agricultural tools and innovations that can help them adapt to stressful conditions that continue to intensify due to climate change. Our support from many organizations such as AGRA helps countries to prioritize, coordinate and effectively implement their national rural development strategies, based on country plans, to achieve this goal. We also believe that engaging in open dialogue with a variety of African voices – including farmers themselves – is critical to our work and will continue to pursue constructive dialogues to address food and nutrition security around common goals and the best ways to achieve them their.”

AGRA did not respond to a request for comment. maintained by AGRA that its cooperation with local small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) is beneficial for seed diversity. The agency says it has supported 2.7 million smallholder farmers to adopt improved soil health practices, including through organic and inorganic fertilizers and drought-tolerant seed varieties. The reports key quantitative achievements in terms of additional investment and economic value mobilized through partnerships (US$141 million), seed sales (123,000 metric tons) and supported SMEs (9,000).

But these kinds of market figures are not the most compelling kinds for those seeking reparations. The signatories to the open letter addressed to the Gates Foundation and others have not specified the details of the damages they are seeking. What they’re looking for extends beyond a dollar amount. At a press conference on August 28 about the open letter, the word “dignity” came up frequently.

One of those who called for the restoration of dignity through the food system was Bishop Takalani Mufamadi, of SAFCEI. “It’s not just monetary, it’s holistic – because we’re trying to restore people’s dignity,” Mufamadi said. He called not only for a change in investment and financial support, but also for the retraining of farmers and the rehabilitation of damaged land. “The reality and the challenge is that these pesticides are destroying not only the land, but also the water table,” he commented.

Mufamadi called AGRA, the Gates Foundation, and seed and agriculture companies “false prophets of food security. They claim to be the messiahs of the hungry and the poor, but have failed miserably due to their approach to industrialization, which degrades lands, destroys biodiversity, and places corporate profits over people. It’s immoral, it’s sinful and it’s unfair.”