“The idea that one becomes stronger through failure is the kind of stern advice people might tell themselves in difficult times,” says strategy professor Kellogg. Benjamin Jones. Indeed, this idea has taken on new life in the “fail fast, fail often” mindset of startups, where it’s accepted that getting out is not just something to be endured, but a critical step on the path to success.

But how true is this widespread belief? And when exactly can failure be a blessing?

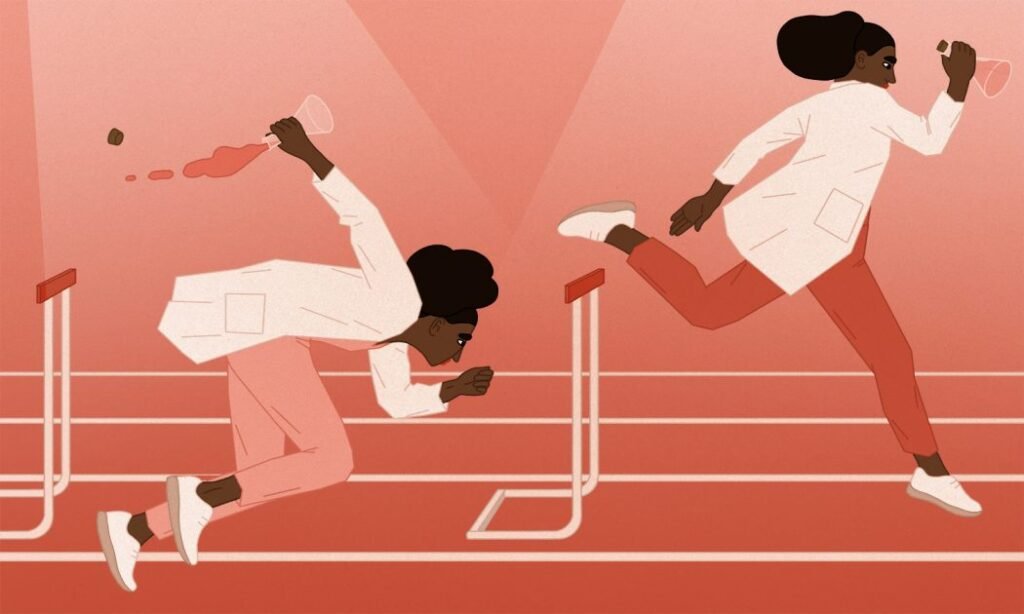

Kellogg faculty examines the surprising benefits of failure and how you can own—and even profit from—your mistakes.

You might be happy to forget early-career setbacks, like that coveted internship you didn’t land or that huge sale you flunked at your first job. (Sorry to remind you.)

But there are signs that these failures may help you in the long run. In a study, professors Dashun Wang and Benjamin Jones and postdoctoral researcher Yang Wang found that early failure can actually lead to later success.

The researchers compared scientists who narrowly missed out on a prestigious federal grant with scientists who nearly qualified for the grant. It turned out that, ten years later, those who didn’t receive the grant ended up publishing more successful papers than those who did.

In the long run, “the losers ended up being better,” says Wang.

Why; The researchers tested several possible explanations—for example, that failure to receive the grant “weeded out” weaker scientists, so that only the highest performers continued to write papers. But even when accounting for this (by artificially eliminating a similar number of scientists who received the grant), the losers still outnumbered the winners.

This left the researchers to conclude that it was adversity itself that drove rejected scientists to succeed. “Failure is devastating,” says Wang, “and it can also fuel people.”

Why do some people who experience failure eventually succeed, when so many others never get over their failure phase?

In another paper, Dashun Wang and Yang Wang, along with their colleagues, developed a mathematical model to identify what separates those who succeed from those who just try, try again. Researchers have found that success depends on learning from one’s past mistakes—for example, continuing to improve parts of an invention that don’t work rather than scrapping them, or identifying which parts of a rejected application to keep and which to rewrite.

But it’s not just that those who learn more as they go have a better chance of winning. Instead, there is a critical turning point. If your ability to build on your previous efforts is above a certain threshold, you will likely succeed in the end. But if it’s even a hair below that threshold, you may be doomed to keep churning out failure after failure forever.

“The people on these two sides of the threshold could be exactly the same kind of people,” says Dashun Wang, “but they will have two very different outcomes.”

Of course, not all failures have a positive effect on your career performance. Sometimes what looks like a setback is actually just a setback. So how can you make lemonade out of the sour lemons of your past?

By weaving them into your personal story, he says Craig Wortman, clinical professor of innovation and entrepreneurship. Convincing potential colleagues that you’d be a great partner and collaborator requires you to tell a coherent, powerful story that encapsulates your strengths – and stories about your failures can help you do that.

When deployed correctly, Wortmann says, your anecdotes of failure can show character, reveal your leadership skills, or demonstrate your drive. So, when is the right time to cheat on one of your failure stories? Maybe when you’re talking to a potential customer, Wortmann says. “By doing that, you show that you’re humble, that you’re a student, and that you’re good to work with.”

For example, Wortmann recalls hearing a CEO tell a “funny failure” story that revealed how he learned the value of asking good questions. The CEO described spending an entire summer talking with a contact at a global consumer packaged goods company, working to cultivate a relationship that he hoped would lead to a major business opportunity. On their fourteenth phone call, he grew impatient and asked his contact when her company would sign the contract—so she informed him that it was a practice.

“She thanked him for everything she had learned that summer,” says Wortmann. “It turned out that it was not a prospect at all. She was a college student. But he never asked her.”

As useful as failure is, that doesn’t mean people are willing to take responsibility for a mess.

Except for the army, that is.

On a visit to the US Army National Training Center, Prof Ned Smith he recalls seeing soldiers of every stripe and rank come forward to incriminate themselves in after-action reviews and debriefings. “It wouldn’t be too much of an exaggeration to say they’re almost competing to take charge,” he says.

Smith and Col. Brian Halloran, former U.S. Army Chief of Staff, senior fellow at Kellogg, looked at how the Army fosters this culture of accountability.

A useful quirk: officers compete throughout the army for promotions. Since the evaluators on the promotion review board do not supervise the officers they evaluate, those officers have less incentive to save face after making a bad call.

“When a leader knows that what matters is the overall performance of the unit and the improvement of the unit as a whole, they are much more likely to openly discuss what went wrong,” says Halloran.

Imagine you’ve spent months developing and perfecting a product. Finally, you hold a focus group to get product reactions, and the focus group participants are excited. Your new product is guaranteed to fly off the shelves — right?

Before you start touting it as “the next big thing,” it might be worth asking who exactly was in that focus group. Professor Eric Anderson has found evidence that there is a class of customers out there who are unusually attracted to products they will never catch. Those people who tended to buy a notorious failed product like Diet Crystal Pepsi were also more likely to buy other doomed products like Frito Lay Lemonade.

Anderson considers these consumers “harbingers of failure,” and for good reason.

“What seems to be happening is that these customers have preferences that may not be mainstream,” he says. “We know that when they really like your product, it shows that your product is really liked by a small group of customers.”

Anderson’s research suggests some simple ways market researchers can eliminate niche products before they have a chance to fall. Importantly, companies should ask customers not only whether they would buy the product in question, but also what other products they buy regularly. A customer who buys Swiffer products, for example, probably has pretty mainstream tastes and should be trusted.

But if the biggest fan of your newest widget is still clamoring for that unusual flavor of beer that’s only been on the shelves for a month, ’cause you probably don’t want to launch that product because it probably won’t have the mainstream appeal it supports. the products for the long term,” Anderson says.