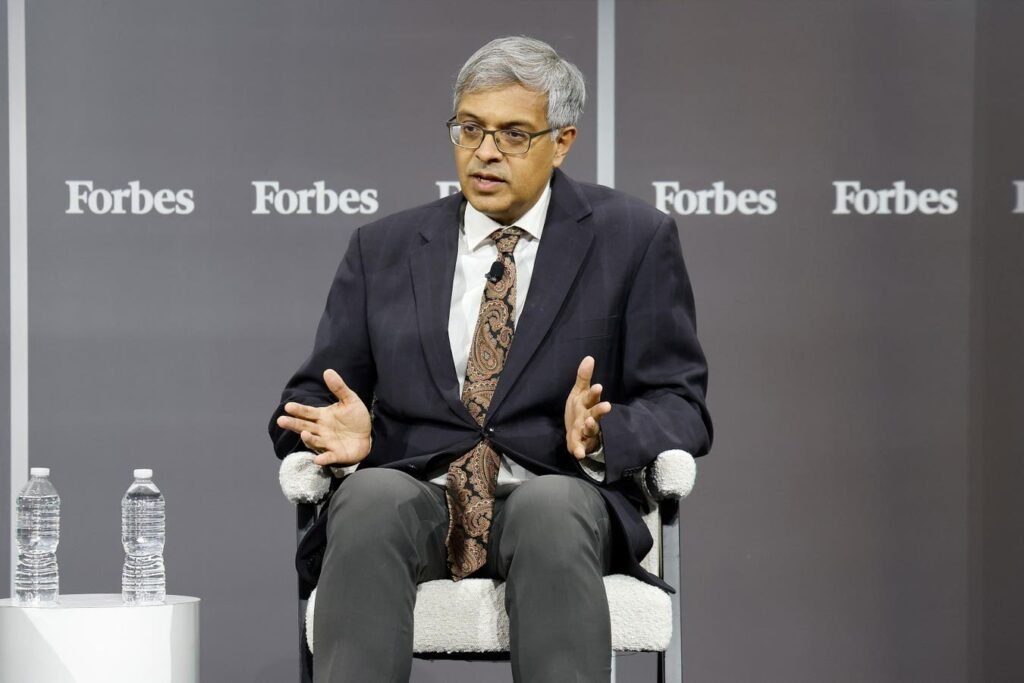

NEW YORK, NY: Jay Bhattacharya speaks during the Forbes Healthcare Summit 2023 at Jazz at … [+]

Getty ImagesJust dismissed as “fringe” by Francis Collins, former Director of the National Institutes of Health, Jay Bhattacharya is President Trump’s pick to lead the NIH, the world’s largest funder of biomedical research. Bhattacharya has a medical degree and is a health economist. He is a professor at Stanford University.

Trump announced Bhattacharya’s selection at Truth Social: “Together, Jay and RFK Jr. they will restore NIH to the Gold Standard of Medical Research as they address the underlying causes and solutions to America’s greatest health challenges, including our chronic disease and illness crisis. Together, they will work hard to make American healthy again!”

Although upheaval at the NIH is likely if Bhattacharya is confirmed by the Senate, the specific direction the agency will take is far from clear.

Republicans in Congress want to reform the NIH and make changes to the ways its $47 billion research budget is distributed. The push for an overhaul of the agency comes in part from a desire to rebuild public trust after perceived failures in handling the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bhattacharya rose to prominence during the COVID pandemic when he became a critic of the public health response. As a co-author of the Great Barrington Declaration in October 2020, before there was a vaccine, he advocated a “focused protection” of those most vulnerable to the coronavirus while letting it spread to other parts of the population to reach herd immunity. Population immunity never happened and many in the science and public health community he complained the policy described in the GBD.

Like many other Republicans, Bhattacharya believes in so-called laboratory leakage theorywhich suggests that the coronavirus originated in a lab in Wuhan, China. The NIH has denied funding for profit-and-loss studies at labs in China that would make a coronavirus more dangerous to humans. In addition, former top NIH officials such as Anthony Fauci have showed you “evidence is accumulating” that the coronavirus was transmitted naturally in a wet market in Wuhan.

But the harsh condemnation remains, with Bhattacharya one of the most vocal critics: “Fire all the people who are currently in charge of pandemic preparedness. They probably caused the pandemic, shut you down, kept your kids out of school, destroyed economies and want more power to do it again,” Bhattacharya posted on X in January this year. And just last week, he added “it is not virtuous to exaggerate an infectious disease threat at the beginning of a pandemic in order to panic the population into compliance. It’s not bad to ask for data to understand the real risk.” Further, in response to his nomination by Trump, he wrote “we will reform America’s scientific institutions so they can be trusted again.”

Perhaps these statements provide clues as to what Bhattacharya may or may not do in relation to policies related to pandemic preparedness. This is certainly important in light of the potential threat that bird flu could pose. But the NIH is much more than an entity that designs ways to design infectious disease outbreaks. It is a driving force behind research aimed at improving public health.

And, as for the hints about NIH reforms that Bhattacharya would pursue, they are hazy at best. It will go along, for example, with what his boss, Health and Human Services Secretary nominee Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has said, and lay off and replace 600 employees at the NIH? Or, as a corollary, would he seek to roughly halve the number of NIH institutes and centers from 27 to 15, as Republican lawmakers have urged?

Republican lawmakers like Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers have embraced it holismwith the goal of eliminating the demographic or disease-specific nature of the current NIH structure, thereby ensuring that each institute examines the whole person and all populations across the lifespan. An example of this is the combination of organs such as the heart, lungs and gastrointestinal tract in a National Body Systems Research Institute.

Also, could Bhattacharya enact Kennedy’s proposed eight-year moratorium on infectious disease research at the NIH so the agency can focus on chronic diseases like diabetes and obesity?

If confirmed, Kennedy will be in charge of HHS, including all 13 functional departments (ten agencies) housed within the department. As was mentioned at Washington Posthe sees it as his mandate to “clean up corruption and conflict in the services and end the chronic disease epidemic.”

Perhaps chronic disease, specifically obesity, would be one of Bhattacharya’s priorities, since more than a decade ago he published several studies examining high costs associated with obesity. He described the difficulties policymakers face when trying to reduce obesity. “Behavioral economists have pointed out that many people lack self-control over their eating and exercise habits. … the optimal population weight and how to achieve it is a complex and controversial issue, full of trade-offs and an area where uninformed engagement with public policy can have unexpected and in some cases unwanted results.’

Here, his nuanced perspective could clash with Kennedy’s expressed view Fox News in October that “if we just gave good food, three meals a day, to every man, woman and child in our country, we could solve the obesity and diabetes epidemic overnight.”

And as evidenced by the federal government’s long history of obesity prevention initiatives that have focused on changing dietary patterns, what’s apparent is that there’s not much new in Kennedy’s proposals other than overblown messaging. Similarly, the HHS Department is engaged in serialization chronic disease initiatives; for many years under successive administrations. Likewise, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has provided much exhibitions for chronic diseases and related expenses.

With the exception of the de-emphasis on pandemic preparedness, particularly around blunt applications of the precautionary principle (a conservative approach to managing risk in the face of uncertainty), the kind of service disruption that NIH director nominee Bhattacharya , will preside, is unclear.