On the award-winning blog, The Chamber of Commerce, Marty Lariviere, a professor of operations at the Kellogg School, has published on the many ways organizations adapt their supply chains to keep their operations running. It also draws lessons from their efforts.

Here are some of our favorite lessons from the past few months.

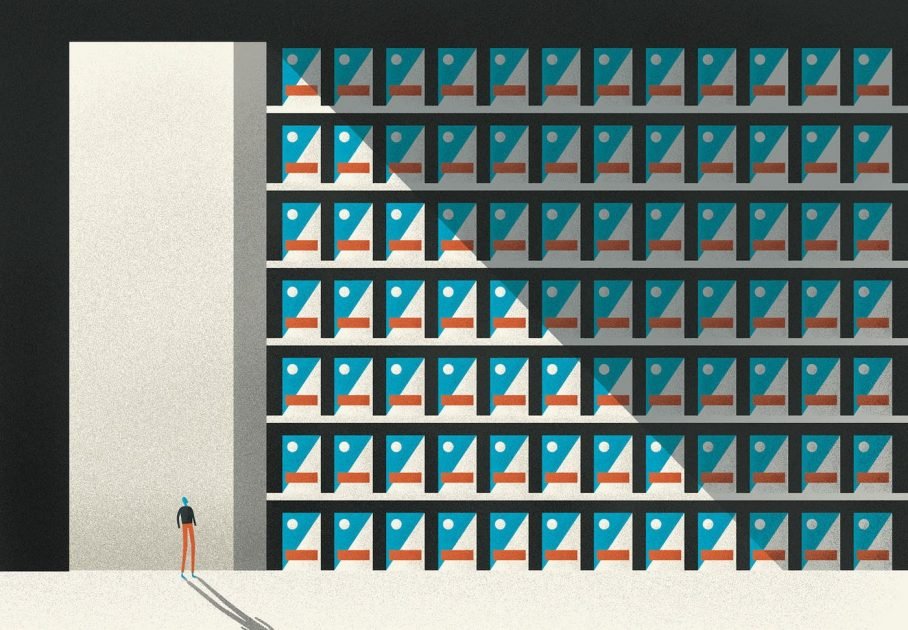

In the first weeks after the pandemic arrived in the US, the nation was hit with critical shortages of PPE, including N95 masks. While rising demand may account for the shortage to some extent, Lariviere writes that a more complex set of factors led to the inventory shortage, including hospitals reducing inventories, manufacturers keeping production lean and the federal government cutting back on inventory. of masks and other materials.

In short, all parties involved favored just-in-time efficiency over durability.

“As hospital networks compete with each other for contracts with insurers, anyone who doesn’t try to save every penny will be at a disadvantage,” Lariviere writes. “A similar logic applies to distributors and producers. An N95 mask is basically a commodity. A given buyer [has] every reason to prefer the cheapest option”.

In the short term, as the pandemic continues to strain supply chains and states see new cases, keeping operations lean will likely take a backseat to staying well-supplied. But the long-term future of PPE storage remains murky.

“It is reasonable to expect that if shortages clear up at some point, various players will have extra inventory for a while,” he writes. “But it’s not clear how long that discipline will last.”

Which leads to the role the federal government could play. As a party concerned with the nation’s long-term response to the pandemic, “they are the ones who could drive some degree of coordination in the supply chain,” he writes.

It’s not just PPE shortages that reveal the downsides of just-in-time manufacturing. In the wake of the pandemic, experts now argue that companies of all kinds have a responsibility to hedge their supply chains against risks.

Lariviere isn’t so sure. He likes a more tailored approach, using the auto industry as an example of a supply chain that probably won’t transform, and the food industry as one that might need an overhaul.

“Having complicated [car] components manufactured in multiple locations sacrifice economies of scale and add complexity for the lifetime of the model,” he writes. “What good is that diversification if you’re actually dealing with a global catastrophe? As the disease spreads, the disorder eventually spreads as well.”

The meat industry, on the other hand – with local factors and unwavering demand – is more likely to change in order to become more resilient to the pandemic.

When countries around the world went into lockdown in the spring, many of us weren’t in the mood to shop for clothes, even online. As a result, clothing brands canceled billions of dollars worth of orders from their global manufacturers, leaving these suppliers in the lurch.

A denim factory in Bangladesh, for example, had to deal with one sudden collapse in demand, despite the fact that it has completed assembly on some jeans and purchased raw materials in advance for others.

“This is essentially about how risk is distributed in a supply chain,” Lariviere writes. “In normal times, suppliers give money to procure materials. That’s why they have to take on debt.” But the same companies have nowhere to turn with product produced for canceled orders.

He describes this as a fundamental asymmetry, which favors Western brands over their suppliers. Lariviere sees this asymmetry as a byproduct of the notion that assembly is not difficult to reproduce.

“The ability to sew is simply an over-commodity,” he writes. “Brands assume they can always find someone else just as capable, so there’s no reason not to drive as hard a deal as possible… Implicit in this is that there’s no value in a long-term relationship with any supplier.”

Speaking of fashion: For companies like British label Boohoo, which specializes in insanely fast product releases, the lockdown has offered an opportunity to pivot quickly to salons. It was able to do this because it had previously moved production to local mini-factories in the East Midlands city of Leicester.

Boohoo could be seen as a success story of a retailer that found a new lane in the crisis.

One problem though. These mini-factories exploited the garment workers, paid them well below the living wage and did not offer safe working conditions.

“As if the abusive labor practices weren’t bad enough, Leicester is under quarantine orders as the rest of the country reopens because the virus is not under control in the city,” Lariviere writes. “This has been linked to the clothing industry and Boohoo in particular.”

Boohoo, Lariviere notes, is essentially bogged down by its own trade-offs between cost, flexibility and ethics.

“It’s hard to do as cheaply as Boohoo needs to do given their price. Difficult, that is, if they play by the rules,” he writes. “So what’s the takeaway here? It may just be that if it seems too good to be true, it probably is.”

The pandemic has hit the craft beer industry very hard. Many bars and taprooms where these craft beer brands build customer loyalty time after time have closed. And in stores, customers are sacrificing taste for price and convenience, opting for the less expensive craft beers that grocery stores carry in larger quantities.

These challenges are formidable. But the pandemic is also exposing weaknesses in the beer industry’s “reverse logistics” system for reusing materials.

First, what happens to all the kegs (owned by the brewers) that are stuck in closed bars? Locating them is part of the puzzle. “There are 20 million barrels in America, and historically brewers didn’t have very tight control over where they were,” Laviriere explains.

Not to mention, what happens to all the beer in those kegs? Who is responsible for picking up the tab on all that stale beer months later?

“You can’t just pour it down the drain, and the industry’s reverse logistics system isn’t really set up to make barrels at home,” Lariviere writes.

*

Read more posts on The Operations Room here.