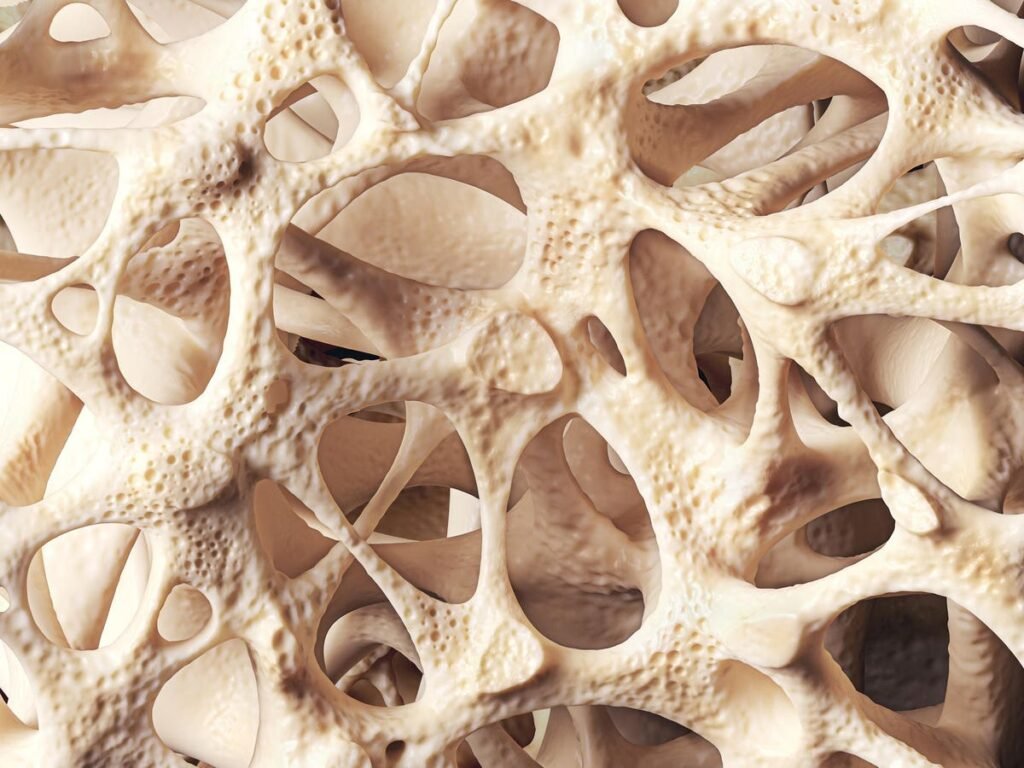

Realistic cancellous bone structure close-up, bone texture affected by osteoporosis, 3D illustration

This article is part of a broad series on recent advances in the science and medicine of longevity and aging. The series covers a range of topics including musculoskeletal health. Expect more articles on bone and muscle regeneration to come.

Our weight rests on our bones. they provide structure to everything else. But with age, the bone marrow becomes less dense and more “fatty”. The result? Brittle bones that are prone to fractures and struggle to repair themselves. However, what happens at the cellular level to cause this deterioration is not well understood. NYU Grossman School of Medicine researchers have now shed light on the underlying mechanisms. Posted in Bone researchoffshoot of Naturetheir work reveals how a signaling pathway that normally helps repair and maintain bones goes haywire as we age, weakening our bones.

Stem Cells and Bone Repair

Bones are special. It is one of the few tissues in the body that can fully regenerated. No scars, no blemishes – as good as new. The unsung heroes responsible for this feat are called skeletal stem and progenitor cells (SSPCs). They are found in the bone marrow, where they help maintain balance and can be called upon to replace old or damaged bone cells. As stem cells, they are defined by their “plasticity”. the ability to develop into many different cell types. Think of them as blank slates that have not yet been given a specific function or purpose. Stem cells found in the bone marrow can differentiate into two different types of cells: osteoblasts, which help secrete the scaffold for bone formation, or adipocytes, which are fat cells that act as energy stores within the skeletal niche. Between the two, our bones are kept in shape and ready to carry us through life.

Unfortunately, the delicate balance between these two types of cells is was discontinued as we age. Stem cells begin to develop a bias, preferentially developing into fat cells over their bone-forming counterparts. This leads to a decrease in mineral density within the bone marrow and an increase in fat content. Indeed, fat cells are actively released signals that hold bone production and regeneration. We are left with “imbalanced” bones that are significantly more fragile and vulnerable to damage.

Notch Signaling: Too Much of a Good Thing?

During early development—while still in the womb—the human body begins to take shape. As part of this process, the skeleton is formed. At first, it is composed entirely of cartilage. It then slowly turns into bone through ossification. Common to all these stages is a signaling pathway called Notch, which helps determine cell fate and cell function. The pathway consists of a family of receptors (Notch1-5) that sit on the surface of cells and facilitate communication between them. Genes involved in this pathway are upregulated during development and help initiate skeletal formation. Alterations or dysfunction of the pathway, in turn, are related a number of skeletal disorders. Once initial development is complete, the signaling pathway is usually downregulated again to allow healthy adult tissue to function. And although the Notch pathway continues to play a role in bone health and maintenance throughout life, it is most active during these early developmental stages.

Given its involvement in bone formation and cell fate, Sophie Morgani, Phd, and her colleagues focused on the Notch pathway as a prime suspect in age-related changes in the bone marrow. The researchers took bone samples from two different age groups of mice: young adult mice (3 months old) and middle-aged mice (12 months old). They chose middle-aged mice instead of old mice (aged 20 months) to identify the factors involved in the progression of aging and bone loss “rather than the end product, the irreversibly aged skeleton.”

As expected, the bone marrow of the middle-aged mice had a higher proportion of adipose tissue than the bone marrow of the young adult mice, suggesting that the skeletal stem cells turned to transform into fat cells. Next, the researchers studied the genes expressed in the bone marrow. Their tests confirmed that key Notch signaling components are upregulated during aging. This was confirmed by both transcriptional and epigenetic assays.

Saving bone health

If dysregulation of Notch signaling drives skeletal stem cells to become adipocytes instead of bone-forming cells, would blocking it help restore bone health?

To test their hunch, the scientists genetically engineered mice to lack them nicastrin. Nicastrin is a protein that activates Notch signaling by cleaving all Notch receptors. like removing the cap from a bottle, the receptors can suddenly start receiving and sending signals. By blocking nicastrin, you block Notch signaling.

Compared to normal middle-aged mice, those lacking nicastrin had significantly less fat in their bone marrow. In addition, their bone mass increased even beyond the levels seen in young mice, and their bones’ ability to heal itself was restored—in effect, the researchers found a way to resist age-related bone degeneration.

The point is that the Notch pathway is involved in a wide range of different systems, tissues and cells. Banning it wholesale would undoubtedly cause unwanted and dangerous side effects. Instead, the researchers were able to identify a protein in the signaling pathway that is relatively specific to skeletal stem cells: Early B-Cell Factor 3 (Ebf3). This protein is downstream of Notch, so its inhibition would have no effect on Notch signaling more broadly. Previous research has noted that the Early B-cell Factor (EBF) family contributes to fat accumulation in the bone marrow. This makes the protein a promising potential therapeutic target.

Packed food

These findings help add an important piece of knowledge to the puzzle of age-related bone loss. Although it was known that skeletal stem cells develop a bias towards differentiating into adipocytes as we age, why this happens has remained unclear. The Notch signaling pathway was the missing link: it becomes dysfunctional with age and contributes to bone loss. Blocking the pathway prevents bone degeneration. The work lays the foundation for additional research to develop therapeutic strategies.