The management pipeline to cover these roles has not gained much more traction for women over the last decade. In 2015, women made up 37 % of the business company work. By 2024, this number increased to 39 %. The representation of women in other categories of management (such as senior directors and vice presidents) was similarly anemic during the same period. Overall, the data suggests that businesses continue to invest more resources for women’s recruitment and promotion of leadership positions.

But not all men and women compete for management positions individually: Many get married and start families who often require a compensation between investment time in their family or careers, he says, he says, he says, he says, he says, he says, he says, Benjamin FriedrichAssociate Professor of Strategy at Kellogg.

“The result of these investments sends signals back to businesses about how dedicated men and women work individually – which businesses could then use to decide who is worth the work that is ultimately based on an administrative position,” he says. “And so it can actually create this kind of reinforcement loop.”

Friedrich and associates of Rune M. Vejlin, Frederik Almar and Bastian Schulz of Aarhus University and Ana Reynoso of the University of Michigan used 25 -year -old data for families and businesses where they worked to attend this family’s interaction.

Their model reacted to the actual gender gap in companies’ roles and found that, among men and women who were equally qualified, women were less likely to receive management training and promotions.

“We are trying to understand what systematic reasons lead to differences between men and women in these achievements in the workplace,” says Friedrich. “Ours is the first frame that puts these two pieces together, taking into account the fact that both couples and companies make strategic choices that are interrelated.”

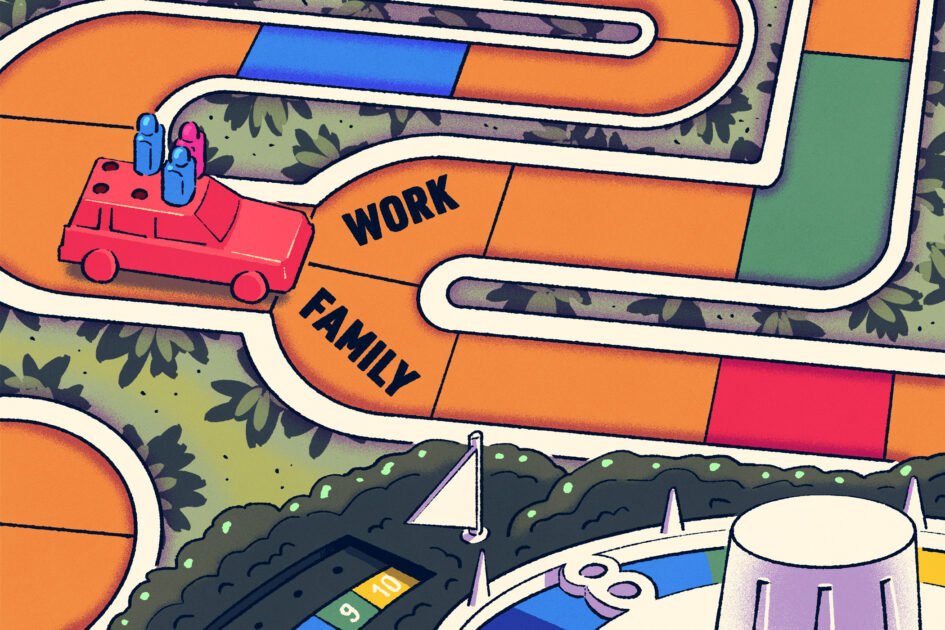

Playing the game of life

Friedrich and his associates displayed a wealthy database from Denmark, which included more than 150,000 people who started their careers between 1991 and 1995 and watched their domestic partnerships and employment orbits over the next 25 years.

“Denmark is a very small country where everything can be collected, accommodated and merged centrally by the Danish Statistical Service,” he says. “The labor market in Denmark is quite similar to the US, so there are many wide standards that we can learn from this small ‘laboratory’.

The researchers then created a mathematical model on how households and companies make decisions about what to invest their resources – and how these decisions affect.

In their model, companies evaluated the value of their employees in three stages: the entry level, the middle career phase and the mature level or the management level. Meanwhile, individual workers made several basic decisions, including their particular career, either getting married, and if they would pull back to work to start a family.

Basically, businesses in the model did not know directly in the way in which working pairs decided to balance their career and family investment together – all companies could see how much time each person puts their jobs over time. And every employee who suddenly leans back their time to work begins to seem less promotable in terms of business.

If this sounds similar to the board game “The Game of Life”, with its trails leading to work and marriage, Friedrich agrees. “It’s absolutely like that,” he says. “The career phases in our model, in important ways, in the life cycle of a household. For example, the first and middle stages of a career – your ’20s and 30s – are also a time when many people work together and have children and this can compete with career investments they would like to do.”

A vicious circle?

When couples work start a family, many face some difficult choices: how much time they will invest at home and not to work and which of them will make the biggest investment. Whether because of the natural requirements or cultural expectations, the mother often hits the brakes in her career. This decision sends a message to companies that make their own tough choices.

‘Not anyone can become a manager, so [firms] You have to choose and choose who to invest, “says Friedrich.” This is a expensive investment that includes high profile assignments and guidance, so the business thinks who will provide the highest possible performance of this training. “

It is not surprising that businesses tend to invest more in employees who put the job first. When women with management potential make the rational decision to repeat the job, companies make the rational decision to put men on the management part-even when both are equally specialized. The decisions of companies, in turn, sends a signal back to households that they can better maximize their own collective profit potential, prioritizing human career.

“You get this feedback loop,” says Friedrich. “One side sends a signal to the other side. This side changes its behavior and then enhances the change behind the other side.”

The model of researchers have had significant gender gaps between the chance of training women and men to get management training and becoming director. But the size of this vacuum varies depending on how ambitious the employee was. In general, the most ambitious workers were more likely to attract business support to become managers.

A scenario where wedding agreements were not implemented: workers married to a more ambitious husband were also more likely to gain support for management management, in part because such families were more likely to delay children. In addition, the researchers found that both of these effects of ambition benefit more than women.

Friedrich and his colleagues found that their model’s behavior fits well with the standards in real world data, which showed that men were 30 percent more likely than women to receive management training and 50 percent more likely to be promoted to administration. “Basically, you simulate what is happening in the model and the results are very similar to the data,” he says.

Two policies

The researchers then used the model to test the impact of two policies aimed at dealing with gender gap. The first was a gender -based quota that required businesses to put an equal number of men and women in management positions. The other was a compulsory parental leave policy for both men and women.

They found that the quota system abolishes gender gaps from design, but also creates implications for women’s career. Forcing companies to promote the equal number of men and women, “households see that more women can become managers – so much from the beginning, it becomes more attractive for many couples to invest in a woman’s career,” says Friedrich. This investment enhances business motives to choose talented women for management training, thus offering even more to promote. In other words, it creates a positive feedback loop to replace the former harmful.

On the other hand, the addition of a political parental leave to the model strongly reduced the gap between men and women – but only when they both had to take it. This is due to the fact that the compulsory license for both parents removes any signal to their employers that one parent is more available (and therefore promoted) than the other. However, this policy also produced lower overall levels of what the model calls households – a general measure of positive outcome – from the imposition of quota. “This means you could really use this as a lever to push towards equality, but households may not like it because they are very invasive,” says Friedrich.

“Understanding these feedback loops is vital to understanding the complete impact of these policies that people have largely discussed,” he adds. “The management quota is quite controversial – some countries have implemented it and some other countries have banned it.

Friedrich warns that the model is not a perfect simulation of reality and that their policies are not a magical realm to end gender gaps in the workplace. Instead, findings must be regarded as a tool for further research.

“Mathematics do not say,” here you have to do “, he says.” You can use it, but you still have to think about what your preferences as a society are. “