Two moose stand next to a large highway underpass where the animals can safely pass under the road … [+]

Rethinking transportation safety and wildlife conservation, the U.S. Department of Transportation is offering $145 million to states with winning ways to help animals get on the road better.

The U.S. government is in the midst of an experiment called the Wildlife Transit Pilot Program and is receiving the first such dedicated federal funding stream. A total of $350 million is projected to be spent on wildlife crossing projects in the US from fiscal years 2022 to 2026.

The current amount of $145 million will go toward the 2024 and fiscal year 2025 projects, while $80 million is set aside for the 2026 grant applications that will be accepted beginning May 1.

Last year’s call for projects was a great success demand from 34 states wanting $549 million—though the allocation exceeded $110 million to pay for 19 projects in 17 states, including those submitted by four Native American tribes.

For any project to succeed, wildlife must want to use human-made bypasses as they travel for migration and other purposes.

The motivation behind this landmark wildlife crossing experiment is the search for technical innovations that work for both states and wildlife to make life safer for everyone who goes about their daily activities.

THE Federal Highway Administration estimates that animal-vehicle collisions cause thousands of serious human injuries, kill 200 Americans annually, and result in $10 billion in economic losses based on reported cases. Unreported animal accidents, if combined, would push those numbers even higher.

The top 10 states with the most drivers who collide with animals annually (based on annual averages and taking into account state and FHWA social cost calculations) are:

· Michigan—54,328 accidents between vehicles and animals annually;

· New York—40,465 accidents;

· North Carolina—21,658 accidents;

· Ohio—20,990 accidents,

· Wisconsin—20,710 accidents;

· Indiana—16,362 accidents;

· Illinois—16,245 accidents,

· Georgia—14,489 accidents,

· Texas—11,614 crashes and

· New Jersey—10,015 accidents.

The three states with the highest rates of known fatal human-animal vehicle crashes each year are Texas, Michigan, and Pennsylvania.

These aggregate statistics reveal the effects of wildlife conflict on humans that are easier to record and document. But it is more difficult to assign a damage value and determine the ecological significance of these accidents for non-human victims.

Birds, for example, are generally not a large component of wildlife crossing mitigation strategies in state departments of transportation. However, vehicle strikes are believed to be among the leading causes of bird deaths. The US Fish and Wildlife Service suggests that between 89 million and 340 million birds die annually from fatal roadway encounters with vehicles, which occur in several scenarios. Birds that live or nest on the ground are destroyed. Winds near bridges blow waterfowl into the path of oncoming cars. Owls hit vehicles because they fly at the height of cars while looking for food. Other birds looking to eat fruit along the roads are poisoned by toxic materials dumped on icy roads in winter.

A study provided to Congress in 2008 identified 21 species (amphibians, birds, reptiles, and mammals) whose survival is directly linked to road kill.

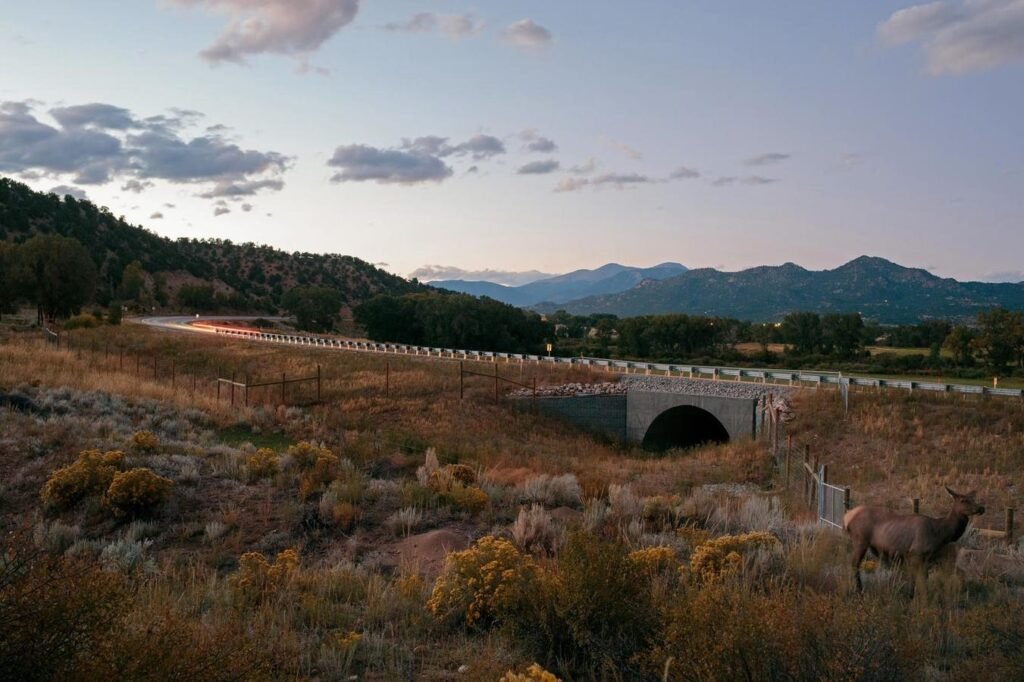

Transportation planners can improve road safety and increase habitat connectivity for wildlife by creating special detours—for mammals, birds, insects, and other critters—to cross over, under, and over roads. away from vehicles. Possibilities include building new structures, remodeling existing ones, creating lane diversions or installing animal warning systems to alert drivers.

A key byproduct of the US government’s wildlife crossing experiment is better connecting habitats for land- and water-dwelling creatures. In some cases, interstates have kept mammal populations (such as antelope, deer, and elk) separated since the 1950s or 1960s, when many national highways were first built. Keeping animals apart can cause genetic problems due to inbreeding and create other health problems that lead to higher mortality rates.

A look at some of the award winners in last year’s wildlife crossing grant shows how state transportation agencies are finding creative solutions to improve safety for drivers and wildlife.

Federal grants awarded to wildlife crossing projects during fiscal years 2022 through 2023 in funding … [+]

For example, Arizona was awarded 24 million dollars for the Interstate-17 Munds Park to Kelly Canyon Wildlife Overpass Project. The plan is to install about 17 miles of wildlife fencing to connect habitat and lower vehicle accidents, especially with deer and elk (which can weigh over 1,000 pounds and cause a lot of damage to passenger vehicles). Other creatures that would benefit from creating a 100-foot wide overpass in Arizona are black bears, bobcats, coyotes, foxes, mountain lions and smaller animals.

Another large grant went to the Wyoming Department of Transportation. He will spend it A $24.4 million federal grant to construct an overpass, several underpasses and high-barrier wildlife fencing along a 30-mile section of rural US 189 to prevent the high rate of wildlife vehicle accidents. Each year 80 reported vehicle collisions occur there associated with seasonal deer movements.

Many transportation planners and wildlife enthusiasts have applauded the federal government’s financial commitment to create more wildlife crossings in the United States.

These innovative transportation construction projects made possible by positive and proactive government action are likely to reap untold benefits and improve safe travel for all.