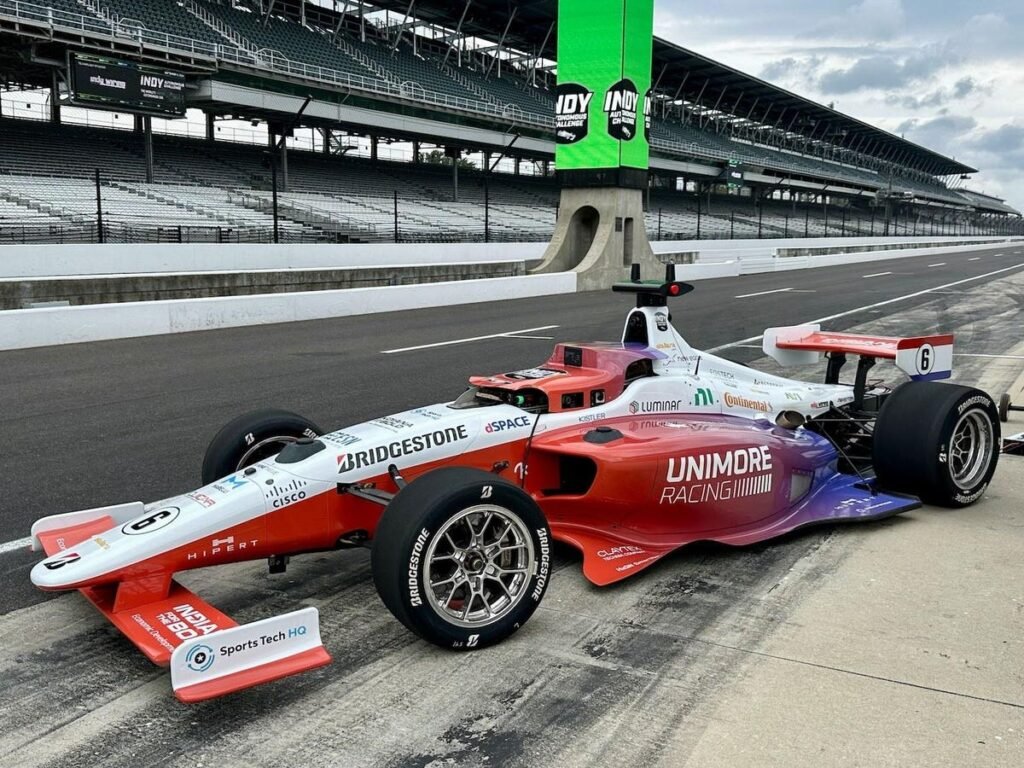

A self-driving race car at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. This car is from the Unimore team from … [+]

The Cavalier Autonomous Racing team from the University of Virginia won the Indy Autonomous Challenge at Indianapolis Motor Speedway yesterday, averaging over 171 mph around the iconic racing oval. The underdog team beat more experienced and successful teams from Germany, Korea, Italy, as well as many other US-based teams from Michigan State University, Purdue, Auburn University, University of California, Berkeley, as well as favorite local Indiana University. was competing for the first time.

“We knew what the car was capable of … when everything looked good for our lap, we had to go for it,” team principal and University of Virginia professor Madhur Behl said after the win. “Today it turns out that was enough for the first American team to win the Indy Autonomous Challenge.”

Final results of the September 6, 2024 Indy Autonomous Challenge time trial at Indianapolis Motor Speedway … [+]

The first Indy 500 was held in 1911 and had a then astonishing average speed of 74.6 miles per hour. Now, over 100 years later, the autonomous race cars used in the Indy Autonomous Challenge have achieved a self-driving car speed record of 192.2 MPH on a straight track. And they zoom around the 2.5-mile Indianapolis Motor Speedway at an average speed of over 170 miles per hour.

These speeds are impressive, but even more so are the participants, a diverse array of students and faculty from some of the world’s leading universities and colleges. Each of them spend hundreds of hours writing code, building systems and analyzing data to navigate cars around the track. The particularly difficult part: they have to do it at speeds that far exceed what self-driving systems like Google’s Waymo, Tesla’s Full Self Driving or General Motors’ Super Cruise must manage.

However, there are rewards.

“It’s not every day you get to work on a real Indy car,” IU Luddy team member Sam Huser from Indiana University told me.

Cars don’t carry a human driver, but they carry a huge amount of technology:

- LiDAR (four sensors)

- Radar (2 sensors)

- Cameras (six)

- High Performance GPS (VectorNav VN-310)

- Cisco IE-3300 switches

- LTE mobile modem

- Intel Xeon server with 14 terabytes of built-in storage

- Drive-by-wire system

- A 488hp Honda racing engine

- Bridgestone tires

I asked Indy Autonomous Challenge president and chairman Paul Mitchell if it was different this time in the third year of the competition.

“We’ve gotten a lot faster,” he said. “These events are important to win hearts and minds, and at some point these technologies will improve our lives.”

A close-up look at the sensor package in self-driving racing cars, capturing what it is … [+]

Much progress has certainly been made. One of the race participants told me that at the inaugural event three years ago, a car started the race and immediately made a hard left turn right into the concrete barrier. At a cost of around $1 million per car, that’s not something organizers want to see happen every day.

In this year’s race, however, all the cars made it around the track. The Indiana State University freshman, the slowest competitor, still managed an average track speed of nearly 125 MPH, an incredible feat for a young team just starting out, and didn’t crash.

There were a few crashes, with a promising team from the University of Munich pushing a little too hard, perhaps, or getting an unlucky gust of wind and ending up in the barrier after a turn. Another car seemingly lost track of where it was and drove over a rock on the inside, but all managed to finish the races at high speed.

Interestingly, the American teams are actually at a disadvantage, an Indy Autonomous Challenge staff member told me. While many of the foreign universities allow students to participate in their teams full-time and skip other courses, American schools require students to continue taking their standard courses.

There were two elements to this year’s self-driving car races.

The first element of the race was a seven-minute track session in which each car could drive alone around the track in an attempt to achieve the highest possible speed, and this was won by the University of Virginia. The second component was a racing challenge in which two cars were on a track trying to beat each other, which was won by the PoliMOVE-MSU team. PoliMOVE-MSU is a multi-school team that includes team members from Politecnico di Milano in Italy, Michigan State University and the University of Alabama.

Head-to-head racing also went up to 170 MPH.

So when will we see traditional car racing with lots of cars on the track, but no drivers? Very soon, according to IAC’s Mitchell.

“Possibly as soon as Las Vegas,” he said. “Definitely in 2025.”

The Las Vegas race is held in early January in conjunction with CES, the Consumer Electronics Show with hundreds of thousands of attendees, so this is an optimistic prediction.

Indy Autonomous Racing has now surpassed 20,000 miles of self-driving car racing, Mitchell says. And autonomous car racing helps average consumers.

“All the hardware in this car is found in business cars today,” he says. “We’re testing this hardware…testing to failure and finding problems with these components.”

The result, he says, is that manufacturers who participate and donate equipment for the IAC get better data that their systems can use in real-world situations, such as high-speed collision avoidance.