What can we make of the new online marketing landscape and how might consumer interactions be transformed?

Jacob Tinyassistant professor of marketing at the Kellogg School, spoke to me Kellogg Insight on advances in ad personalization, the ways tech companies are rethinking their privacy policies, and the rise of authenticity.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Kellogg Insight: What current trends are you following most in the digital marketing space? How do you see these trends affecting the broader marketing landscape?

Jake Tinney: These days, I’ve become interested in people’s privacy concerns.

Privacy is a bit of a paradox, because while people say they are concerned about the privacy of their data, most never do anything about it. Researchers attribute this in part to an evolutionary predisposition. When we lived in smaller groups, we had to worry a lot about our social standing because we could be kicked out of the group, which could lead to death. Today, we still have the remnants of this, even if the consequences of a bad reputation are not as dire as they used to be. It is this residual effect of our evolutionary psychology that has not quite adapted to the widespread diffusion of data today.

However, another important part in this “privacy paradox” is that some very basic sites leave us little options to give details if we want to use them.

This changes somewhat, as well companies like Apple and Google are changing some of the tools they use to track people. In fact, I was talking to a former marketing executive at Apple and I asked him, “Why are you pushing for privacy? This from the research doesn’t seem to matter much in terms of changing user behavior.” He said, “To be honest, it was a completely internal decision. We felt this was an unhealthy way to process consumer data and wanted to take a stand.”

Now, of course, Apple has certainly put a lot of emphasis on privacy in their advertising, so I’m sure they had nothing more in mind than the well-being of consumers.

But whatever the reason, it’s going to be a little harder for people to track and for advertisers to monetize or personalize their ads, even though we’re now in the age of personalization.

Insight: How representative is Apple’s stance on consumer welfare? Do you think many companies are trying to boost their reputation and gain consumer trust?

Teeny: Not everyone takes such an outward stance on privacy, as many companies benefit from access to this data. But I think this question ties into another broad trend we’re seeing, particularly in online marketing, which is trying to develop a sense of authenticity as a brand. Almost every brand has to support something these days. One way you can do this is by trying to take an authentic position on an issue, whether it’s fair labor practices or sustainability, or in Apple’s case, privacy, in order to see yourself as legitimate.

Insight: If I’m a brand, what can I do to develop that sense of authenticity beyond just saying, “Yes, I support this social issue?” What specific steps can I take with my online audience to engage them with a transparent and coherent sense of what I stand for?

Teeny: Well, there are a few recently research to suggest that live or disappearing videos on social media are perceived by audiences as a little more authentic.

But brands can also tell stories. I think there’s a big push towards storytelling now, not only because it helps cut through the clutter of online advertising, but also because when you tell a story, it feels more authentic. It makes you seem more like a person and less like a disconnected third-party body. It helps you seem more trustworthy and enjoyable, like a friend who is going to give you advice on what to buy.

Insight: This sounds like brands—whether they’re selling soap or soft drinks—are thinking a lot about how to make customers feel.

Teeny: Yes, emotions are very important in marketing! In advertising, we often talk about “ladder” ads. For example, when you introduce a product, you first describe its features, then you can “move up” to the functional benefits of those features, then to the emotional benefits of those features, and finally to the higher-order purpose of the product. But today, I think we’re seeing a lot more brands spend less time in that functional stage and more in that emotional stage, just because there are so many different products and markets out there that serve a similar function. You need to stand out or differentiate yourself in some way immediately.

In psychology, there is a phenomenon called the pratfall result where essentially introducing a small character flaw makes you more likable because people can’t relate to you when you’re just shiny and perfect.

I think we see that with brands, where they’re more open about their mistakes, which seems like a consequence of the ever-watching gaze of social media. It’s a way to build reality, by being a little further off the cuff.

Insight: What factors do you think complicate the ability of brands to pursue authenticity? Are there regulatory or industry standards forcing marketers to adapt or companies to rethink?

Teeny: Well, there is a history in the US and elsewhere of advertisers being manipulative. As consumers, we know that marketers will try to tell us what we want to hear.

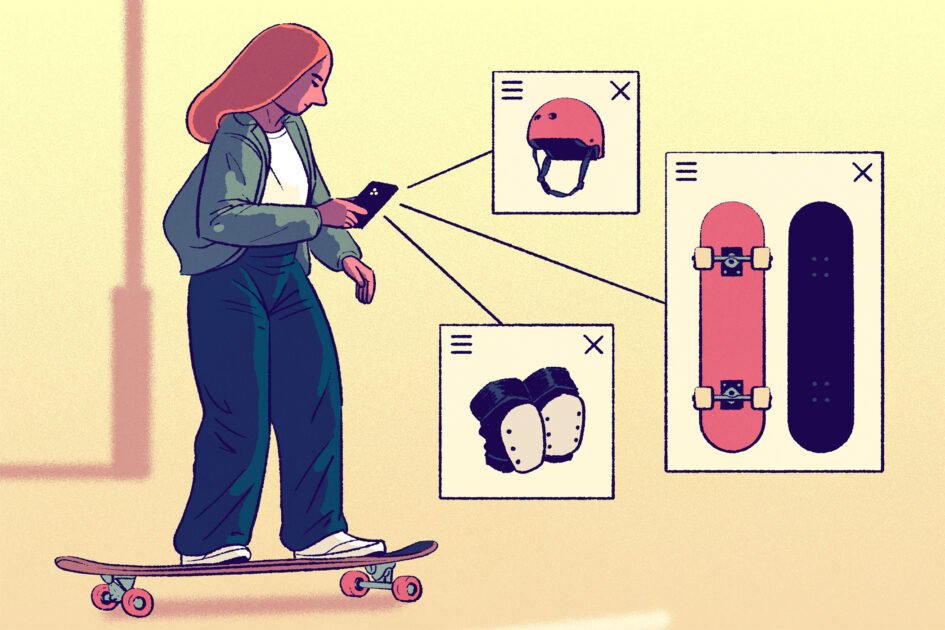

I think this was a big problem with ad personalization a few years ago. A lot of people didn’t like custom ads at first. They felt like “oh, you’re stomping on my data and trying to manipulate me into what I’d like.” Now, about 70 percent of consumers prefer personalized ads. They say, “if you’re going to show me an ad, at least show me something I’m actually interested in.”

Insight: Is there a danger that companies are overplaying their hand in this particularity?

Teeny: As I said earlier, in the beginning, any form of personalization was offensive. Now, a moderate amount is fine, but anything in excess is bad. For example, there is consistent finding that using data that people think should be completely inaccessible, like your banking or financial statements, to personalize an ad really turns people off. Something like, “We noticed that you make 30 euros a year. Here is our special.” People really don’t like that.

But it will probably get to the point one day where that’s okay too. It’s all about our expectations. Once companies have their foot in the door, incremental increases are more acceptable.

Insight: At the moment, personalization seems reactive. I buy a pair of shoes and for the next six months I get sneaker ads everywhere on all my social media channels. In what ways are companies seeking to become more predictive about this to become more relevant to the customer?

Teeny: The issue you raise about unnecessary targeting is a fertile one throughout the marketing industry and is really a matter of bad AI. The reason repurchase behavior is so prioritized now is because that’s what marketers have been able to intuitively—and even statistically—identify as a strong predictor of what people will buy again.

I think we’ll see better forms of targeting as AI gets better and more widespread. Eventually, more sophisticated algorithms will allow people to be much sharper and much clearer in the types of marketing and analytics tools they use. They’ll find factors you might not have expected that can strongly predict a personalized sale.